Nero’s Killing Machine by Stephen Dando-Collins

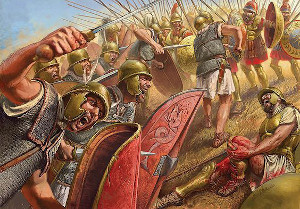

I’d heard of the glory of Rome but after reading this I now understand that there was no such thing; only enough slaughter, slavery, greed, assassination and suicide to shake you to the core. Such a horrible people in such horrible times!

This is a history of Rome’s XIIIIth legion (take note, not XIVth). Founded by no lesser celebrity than Julius Caesar in 58 BCE, we follow it through victory and defeat (but mostly terror and horror) for about 500 years until Rome finally gets its just desserts.

I found the book tedious at times, stuffed as it is with long lists of the bit players and the postings of the legions hither and thither across Europe. However, to contradict that assessment, I also found it fascinating that we know so much about them, right down to the bit players. The book is, I think, intended to entertain us, so we are not smothered in references but I expect that it is an honest rendering of what the sources say; of course the objectivity of the sources is probably suspect, many of them being Roman citizens. I found myself frequently disbelieving the metrics of how many participated in battles and how many were killed. I also couldn’t believe the constant assurances that the legionaries were keen to go to battle. One message I got from the suicides was that it was by far the least frightful way to die.

It engaged me enough to stick with it to the end and indeed to start me wondering what my next Roman history book will be.

This rip-roaring tale is presented as real history and despite the partisan writing I believe it to be true enough. It presents a band of Irish patriots, including John Devoy, who decide the gesture of rescuing these men is worth the danger of being caught themselves and the outrageous cost involved in buying a ship and sailing to the other side of the planet. One lunatic who wanted to be in the mission, but was rejected, even gets there under his own steam! Their plan is naive but it works and their exploit is celebrated in America, Australia and Ireland to the chagrin of the Brits. It is mystifying and deeply heart-warming to read how much personal risk ordinary men with no stake in the affair were prepared to take.

This rip-roaring tale is presented as real history and despite the partisan writing I believe it to be true enough. It presents a band of Irish patriots, including John Devoy, who decide the gesture of rescuing these men is worth the danger of being caught themselves and the outrageous cost involved in buying a ship and sailing to the other side of the planet. One lunatic who wanted to be in the mission, but was rejected, even gets there under his own steam! Their plan is naive but it works and their exploit is celebrated in America, Australia and Ireland to the chagrin of the Brits. It is mystifying and deeply heart-warming to read how much personal risk ordinary men with no stake in the affair were prepared to take.

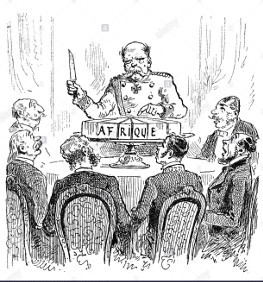

What a great read! I was well prepared for this book. I’ve read Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness, H.G.Wells’ War of the Worlds and Adam Hochschild‘s King Leopold’s Ghost. Sometimes I knew what I was reading, sometimes the deeper message eluded me.

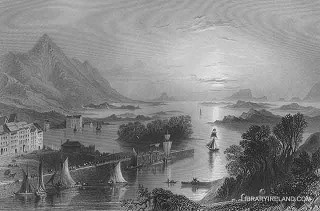

What a great read! I was well prepared for this book. I’ve read Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness, H.G.Wells’ War of the Worlds and Adam Hochschild‘s King Leopold’s Ghost. Sometimes I knew what I was reading, sometimes the deeper message eluded me. Des Ekin takes us on a clockwise tour of the coast, recounting in a jocular, chatty manner the various scoundrels that plagued shipping since the 12th century. The light-hearted style belies the very serious research attested to by the copious endnotes provided.

Des Ekin takes us on a clockwise tour of the coast, recounting in a jocular, chatty manner the various scoundrels that plagued shipping since the 12th century. The light-hearted style belies the very serious research attested to by the copious endnotes provided. It’s an astonishing piece of work in the form of a diary running from October ’43 to October ’44 and recording the experience of Lewis as an NCO in the Field Security Service (a branch of the Intelligence Corps) just after the arrival of the American and British in Italy. Lewis is clearly a humanist and is appalled and sickened by the ineptitude, cowardice, corruption, poverty and indifference he encounters everywhere. Italy comes across as another planet, with extraordinary superstitions and religious fervour living side by side with vendettas, omertà and injustice. The old, the poor and most of all, the women, suffered unimaginable outrages.

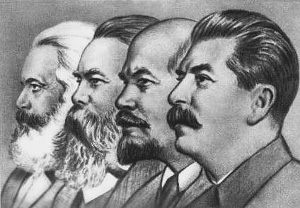

It’s an astonishing piece of work in the form of a diary running from October ’43 to October ’44 and recording the experience of Lewis as an NCO in the Field Security Service (a branch of the Intelligence Corps) just after the arrival of the American and British in Italy. Lewis is clearly a humanist and is appalled and sickened by the ineptitude, cowardice, corruption, poverty and indifference he encounters everywhere. Italy comes across as another planet, with extraordinary superstitions and religious fervour living side by side with vendettas, omertà and injustice. The old, the poor and most of all, the women, suffered unimaginable outrages. The book splits into three parts: the gestation and execution of the Revolution, the Stalin years and the decline of the regime. I would say that the first section was pitched at about the right level for me but that the writer overindulged himself somewhat in spelling out the horror of the Stalin years, very much at the expense of the final section which, insofar as it went, I found newest and most appealing. Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin all get crammed into a few (very interesting) pages where I’d have like to have heard more. He quotes Alexis de Tocqueville (1856):

The book splits into three parts: the gestation and execution of the Revolution, the Stalin years and the decline of the regime. I would say that the first section was pitched at about the right level for me but that the writer overindulged himself somewhat in spelling out the horror of the Stalin years, very much at the expense of the final section which, insofar as it went, I found newest and most appealing. Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin all get crammed into a few (very interesting) pages where I’d have like to have heard more. He quotes Alexis de Tocqueville (1856):