This is book that “does what it says on the tin” for the British Welfare State. I had assumed that the creation of the Welfare State in 1948 was largely a response to the challenges coming from the communist revolution and the development of state planning, equality of treatment for all i.e.delivery of health services determined by need rather than ability to pay.

This book starts in the 18th century and shows the slow evolution of thought and developments that finally lead us to the launching of the NHS in 1948, from initial views of poverty being assumed to be character related (the indigent for the poorhouse)to a gradual understanding of (some) of the complexities that are inherent in poverty and associated health issues.

I liked the book but maybe that’s because I like reading about history. I was certainly better informed and my initial assumptions were shown to be totally inadequate. I am sure the communist revolution had some influence but the story has a much longer pedigree than I assumed.

Tag: History

Strategy Classroom

Review: Afghan Guerilla Warfare: Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet Afghan War by Ali Jalali and Lester Grau

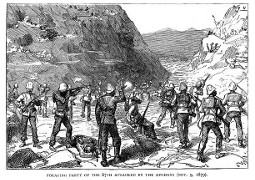

Shortly after Russia withdraw from Afghanistan, the US Marine Corps sent some officers to the country to interview frontline Mujahideen leaders. The idea was to get an insight into how the guerrilla war was conducted and to then incorporate that knowledge into counter-insurgency training back in the US. This book contains details of about 100 mujahideen ambushes in the words of people who were present. The ambushes are mostly described in less than three pages apiece. Many include maps and although not chronologically listed, the evolution in tactics used by both sides in the conflict is very clear. This is a story of the triumph of a lightly armed indigenous population over an invading army which possessed superior firepower, the story of a cause defeating a professional army and perhaps confirmation of the adage that those who can endure the most will ultimately prevail.

Shortly after Russia withdraw from Afghanistan, the US Marine Corps sent some officers to the country to interview frontline Mujahideen leaders. The idea was to get an insight into how the guerrilla war was conducted and to then incorporate that knowledge into counter-insurgency training back in the US. This book contains details of about 100 mujahideen ambushes in the words of people who were present. The ambushes are mostly described in less than three pages apiece. Many include maps and although not chronologically listed, the evolution in tactics used by both sides in the conflict is very clear. This is a story of the triumph of a lightly armed indigenous population over an invading army which possessed superior firepower, the story of a cause defeating a professional army and perhaps confirmation of the adage that those who can endure the most will ultimately prevail.

This book should appeal to anyone interested in strategy or indeed anyone who wants to understand something about the people of Afghanistan and the conflicts of recent decades. Coincidentally, many of the place names mentioned, feature again in the more recent Afghanistan conflict and probably some of those who co-operated in the book found themselves subsequently opposing US & UK forces post 9/11.

Hysterical Blindness

Review: The Man Who Invented Hitler by David Lewis

In October 1918, Adolf Hitler is blinded in a gas attack on the western Front. Hitler presents with no physical damage to the eyes and is assessed to be suffering from a condition known as hysterical blindness. He is referred to Dr. Edmund Forster, an experienced army psychiatrist and neurologist known for his ‘shock treatment’ approach to curing patients. Forster successfully ‘cures’ Hitler. The premise of the book is that Forster’s treatment created a new psychologically very different Hitler and thus changed history.

In October 1918, Adolf Hitler is blinded in a gas attack on the western Front. Hitler presents with no physical damage to the eyes and is assessed to be suffering from a condition known as hysterical blindness. He is referred to Dr. Edmund Forster, an experienced army psychiatrist and neurologist known for his ‘shock treatment’ approach to curing patients. Forster successfully ‘cures’ Hitler. The premise of the book is that Forster’s treatment created a new psychologically very different Hitler and thus changed history.

While we do learn about Forster, the book heavily focuses on Hitler. We get a good overview of his formative political years and also the changing face of Germany post-WW1. The story ends with the suicide in strange circumstances of Dr. Forster in 1933 shortly after the Nazis assumed full control of Germany. The suicide removed someone who knew too much about Hitler’s past. An interesting ‘what if’ in the book is a verified account of an incident in which a British soldier had Hitler in his gunsights but opted not to shoot as Hitler was already wounded.

50 Shades of Enlightenment

Napoleon the Great by Andrew Roberts

The Dream of Enlightenment by Anthony Gottlieb

Two Fine Men by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

We often imagine we live at the most exciting time in history where change is constant and succeeding generations have entirely different life experiences. In previous centuries, change was slow. However, that’s not what my reading of the last several months tells me. I’ve become obsessed with the Enlightenment, an amazing time when the modern world was invented, where human rights mounted on the stage and science replaced religion. I’ve been reading it as philosophy, as history, as biography and even as adventure novel.

Gottlieb’s book is a decent roundup of the enlightenment thinkers, indispensable for me as I knew so little about them. Pérez-Reverte’s novel describes two gentlemen travelling from Madrid to Paris in 1780 to buy all 28 volumes of Diderot’s proscribed Encylopédie and the efforts of the establishment, whose social and cultural hegemony was threatened by new ideas, to thwart them.

However the most daunting (800 pages) but immensely satisfying of the three books is Roberts’ amazing biography. Where I expected to be affronted by wild ambition, cruelty and arrogance, I encountered Enlightenment Man. Yes, he was a military genius, but that’s of little interest to me. He was that thing, a benevolent dictator, which probably cuts little ice among 21st century liberals. The thing is: he lasted long enough (16 years) to establish the ideals of the French Revolution which had been subverted in the Reign of Terror so that even after the restitution of the monarchy, they couldn’t be undone. This book makes it clear it was the genius of Napoleon and his ability to be interested in the minutiae of his world that allowed him create a legacy that endured. The most amazing discovery for me was his charisma and generosity. I liked him, most of the time.

However the most daunting (800 pages) but immensely satisfying of the three books is Roberts’ amazing biography. Where I expected to be affronted by wild ambition, cruelty and arrogance, I encountered Enlightenment Man. Yes, he was a military genius, but that’s of little interest to me. He was that thing, a benevolent dictator, which probably cuts little ice among 21st century liberals. The thing is: he lasted long enough (16 years) to establish the ideals of the French Revolution which had been subverted in the Reign of Terror so that even after the restitution of the monarchy, they couldn’t be undone. This book makes it clear it was the genius of Napoleon and his ability to be interested in the minutiae of his world that allowed him create a legacy that endured. The most amazing discovery for me was his charisma and generosity. I liked him, most of the time.

So when we plan our Christmas lunch and do that “who from history would you invite?” thing, I want Napoleon there.

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan

The full title of the book is “The Silk Roads: A new history of the world”. The primary aim of the book as stated by the author is to shift our focus from the Eurocentric view of history back to the EurAsian landmass with an initial focus on the early civilisations, particularly Persia.

The underpinning basis of the analysis is materialist/economic rather than military and political and revolves around the Silk Roads running from the Near East to China. The importance of the Silk Roads was critical for thousands of years, became somewhat subdued and less important following the discovery of the New World(s) and significantly improved sailing capabilities but is now in the process of reasserting its significance. The book is ambitious – a new history of the world in 600+ pages – so we move through the centuries reasonably briskly – but is full of anecdotal detail to emphasise or capture the essence of the time.

I thought the first half of the book was very good, particularly as the focus is on trade it gives a different historical perspective. The research is impressive: what else would you expect from a Professor of Byzantine Studies at Oxford. I found the second half of the book somewhat underwhelming and predictable. I also found the book quite Eurocentric despite its stated aim. There is not any analysis of China, or the impact of the Silk Roads on China and not a lot on Central Asia (the Stans etc) other than they became rich as intermediaries on the trade routes. On balance, I enjoyed the book and thought it a worthwhile read.