Days by James Lovegrove

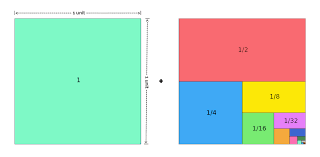

Days is a megastore owned and run by the 7 days brothers in a mega-consumerist world not unlike our own. Everything that can be sold (from wild animals to prostitution passing via the more mundane is sold there). We follow a member of Strategic Security and a newly admitted store-card-holder through a single day.

The first three-quarters of the book is slow but mildly amusing as the scaffolding is put in place to administer a resounding dénouement. Store security begins its day with a Hills Street Blues style roll-call, warning plain-clothes store detectives the current scams to look out for. Customers are credit-rated and get card types reflecting their purchasing power. Even the trolleys have to be rented for use. A Days card is the ultimate status symbol and the author has great fun mocking consumerism, not least during flash-sales when customers have 5 minutes to obtain bargains in some department which lead to stampedes and fist fights.

Everything builds to quite a dramatic but unconvincing and rather silly climax. A grand disappointment.