Review: Scum of the Earth by Arthur Koestler

By the end of his flight across Europe, Koestler had coined this rather telling (and desperate) motto: Let humanity get by without my help.

This is a staggering book about his experiences in France during the first year of WWII as he was pushed around by bureaucrats, interned and generally made to understand he was the scum of the earth. His first book in English, I’d give anything to write with his mastery. Born into wealth in Hungary, he lived through Hell both before and after the war, chalking up among his experiences a death sentence during Spanish Civil War. This amazing book (despite chapter titles such as Agony, Purgatory and Apocalypse) manages to convey stoic-ness (is that a word?) and even humour. The book is dedicated to comrades of his ilk (intellectuals, authors and idealists) who for the most part did not manage to endure their conditions and succumbed to suicide.

And the cleverness of the title: who are the scum of the earth? The idealists who fled from fascist Europe to expected safety in France or the French authorities and their minions who betrayed them?

Unputdownable. Much of the book had me reflecting on the experience of refugees in Ireland in this 21st century, whose experiences must at least reflect his to some degree.

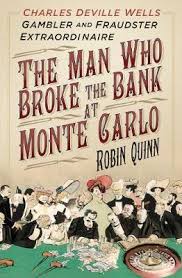

Review: The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo by Robert Quinn.

Review: The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo by Robert Quinn. However the most daunting (800 pages) but immensely satisfying of the three books is Roberts’ amazing biography. Where I expected to be affronted by wild ambition, cruelty and arrogance, I encountered Enlightenment Man. Yes, he was a military genius, but that’s of little interest to me. He was that thing, a benevolent dictator, which probably cuts little ice among 21st century liberals. The thing is: he lasted long enough (16 years) to establish the ideals of the French Revolution which had been subverted in the Reign of Terror so that even after the restitution of the monarchy, they couldn’t be undone. This book makes it clear it was the genius of Napoleon and his ability to be interested in the minutiae of his world that allowed him create a legacy that endured. The most amazing discovery for me was his charisma and generosity. I liked him, most of the time.

However the most daunting (800 pages) but immensely satisfying of the three books is Roberts’ amazing biography. Where I expected to be affronted by wild ambition, cruelty and arrogance, I encountered Enlightenment Man. Yes, he was a military genius, but that’s of little interest to me. He was that thing, a benevolent dictator, which probably cuts little ice among 21st century liberals. The thing is: he lasted long enough (16 years) to establish the ideals of the French Revolution which had been subverted in the Reign of Terror so that even after the restitution of the monarchy, they couldn’t be undone. This book makes it clear it was the genius of Napoleon and his ability to be interested in the minutiae of his world that allowed him create a legacy that endured. The most amazing discovery for me was his charisma and generosity. I liked him, most of the time.